Genealogies of the Early Families of Weymouth, Norfolk, Massachusetts

Tim White is continuing with a group of restless men atop a ridge in the Afar desert of Ethiopia. A few of them are pacing back and along, straining to see if they can spot fragments of biscuit bone in the reddish-brown rubble below, as eager to start their search as children at an Easter egg hunt. At the lesser of the hill is a 25-foot-long cairn of black rocks erected in the style of an Afar grave, so large it looks similar a monument to a fallen hero. And in a style it is. White and his colleagues assembled information technology to mark the place where they first establish traces, in 1994, of "Ardi," a female who lived 4.four million years ago. Her skeleton has been described every bit ane of the most important discoveries of the by century, and she is irresolute basic ideas almost how our earliest ancestors looked and moved.

More than xiv years later, White, a wiry 59-year-old paleoanthropologist from the Academy of California at Berkeley, is hither again, on an almanac pilgrimage to meet if seasonal rains have exposed whatsoever new $.25 of Ardi's basic or teeth. He often fires upwardly the fossil hunters who work with him by chanting, "Hominid, hominid, hominid! Go! Get! Become!" Merely he can't let them become all the same. Only a week earlier, an Alisera tribesman had threatened to impale White and ii of his Ethiopian colleagues if they returned to these fossil beds near the remote village of Aramis, home of a clan of Alisera nomads. The threat is probably only a bluff, simply White doesn't mess with the Alisera, who are renowned for being territorial and settling disputes with AK-47s. As a precaution, the scientists travel with six Afar regional police officers armed with their own AK-47s.

Arranging this meeting with tribal leaders to negotiate access to the fossil beds has already cost the researchers 2 precious days out of their 5-week field flavor. "The best- laid plans change every 24-hour interval," says White, who has also had to deal with poisonous snakes, scorpions, malarial mosquitoes, lions, hyenas, flash floods, dust tornadoes, warring tribesmen and contaminated food and water. "Aught in the field comes easy."

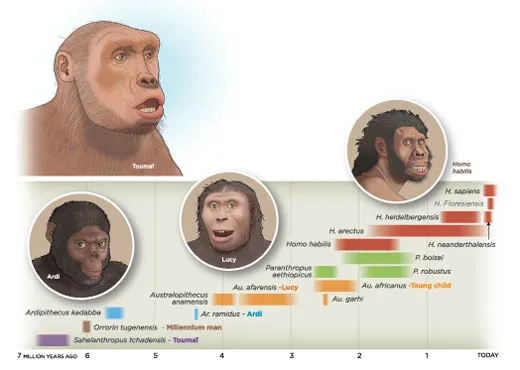

Equally we look for the Alisera to arrive, White explains that the squad returns to this hostile spot year afterwards yr considering it's the only identify in the world to yield fossils that span such a long stretch of human evolution, some six 1000000 years. In improver to Ardi, a possible direct ancestor, it is possible hither to observe hominid fossils from as recently equally 160,000 years ago—an early Man sapiens like united states—all the way back to Ardipithecus kadabba, 1 of the earliest known hominids, who lived most half-dozen million years ago. At last count, the Middle Awash project, which takes its name from this patch of the Afar desert and includes 70 scientists from 18 nations, has found 300 specimens from seven different hominid species that lived here 1 afterwards the other.

Ardi, short for Ardipithecus ramidus, is now the region'due south all-time-known fossil, having fabricated news worldwide this past autumn when White and others published a serial of papers detailing her skeleton and ancient environment. She is not the oldest member of the extended human family, but she is by far the near complete of the early hominids; most of her skull and teeth as well as extremely rare bones of her pelvis, hands, arms, legs and feet have so far been found.

With sunlight first to bleach out the gray-and-beige terrain, we see a cloud of dust on the horizon. Shortly 2 new Toyota Country Cruisers pull upwards on the promontory, and a 6 Alisera men jump out wearing Kufi caps and cotton sarongs, a few cinched up with belts that also hold long, curved daggers. About of these association "elders" appear to be younger than 40—few Alisera men seem to survive to sometime age.

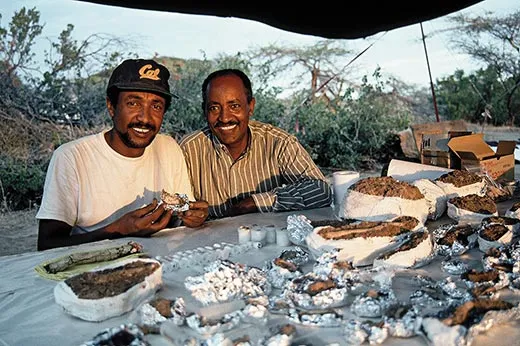

Afterward customary greetings and handshaking, White gets downward on his hands and knees with a few fossil hunters to show the tribesmen how the researchers crawl on the ground, shoulder to shoulder, to look for fossils. With Ethiopian paleoanthropologist and project co-leader Berhane Asfaw translating to Amharic and another person translating from Amharic to Afariña, White explains that these stones and bones reveal the ancient history of humankind. The Alisera smiling wanly, patently amused that anyone would desire to grovel on the footing for a living. They grant permission to search for fossils—for now. Just they add one caveat. Someday, they say, the researchers must teach them how to go history from the ground.

The quest for fossils of homo ancestors began in hostage after Charles Darwin proposed in 1871, in his book The Descent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex activity, that humans probably arose in Africa. He didn't base of operations his claim on hard testify; the merely hominid fossils and then known were Neanderthals, who had lived in Europe less than 100,000 years ago. Darwin suggested that our "early on progenitors" lived on the African continent considering its tropical climate was hospitable to apes, and considering anatomical studies of modern primates had convinced him that humans were more than "centrolineal" with African apes (chimpanzees and gorillas) than Asian apes (orangutans and gibbons). Others disagreed, arguing that Asian apes were closer to modern humans.

Equally information technology happened, the starting time truly aboriginal remains of a hominid—a fossilized skullcap and teeth more one-half a million years one-time—were found in Asia, on the island of Java, in 1891. "Java homo," as the brute was called, was later classified as a member of Homo erectus, a species that arose 1.8 million years agone and may accept been one of our direct ancestors.

And then began a century of discovery notable for spectacular finds, in which the timeline of human prehistory began to take shape and the debate continued over whether Asia or Africa was the human birthplace.

In 1924, the Australian anatomist Raymond Sprint, looking through a crate of fossils from a limestone quarry in South Africa, discovered a small skull. The first early hominid from Africa, the Taung kid, as information technology was known, was a juvenile fellow member of Australopithecus africanus, a species that lived 1 meg to 2 million years ago, though at the fourth dimension skeptical scientists said the chimpanzee-size braincase was as well small for a hominid.

In 1959, archaeologist Louis Leakey and his wife Mary, working in Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, discovered a bit of hominid jawbone that would later become known as Paranthropus boisei. The 1.75-million-year-former fossil was the first of many hominids the Leakeys, their son Richard and their associates would find in East Africa, strengthening the case that hominids indeed originated in Africa. Their work inspired American and European researchers to sweep through the Not bad Rift Valley, a geologic error that runs through Kenya, Tanzania and Ethiopia and exposes stone layers that are millions of years erstwhile.

In 1974, paleoanthropologists Donald Johanson and Tom Grayness, excavation in Hadar, Federal democratic republic of ethiopia, plant the partial skeleton of the primeval known hominid at the time—a female they chosen Lucy, later the Beatles' song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds," which was playing in camp as they celebrated. At iii.2 million years quondam, Lucy was remarkably primitive, with a encephalon and trunk about the size of a chimpanzee's. Just her ankle, knee and pelvis showed that she walked upright like the states.

This meant Lucy was a hominid—only humans and our close relatives in the man family habitually walk upright on the footing. A member of the species Australopithecus afarensis, which lived from 3.9 one thousand thousand to two.9 meg years ago, Lucy helped respond some fundamental questions. She confirmed that upright walking evolved long earlier hominids began using stone tools—about 2.half dozen meg years ago—and before their brains began to expand dramatically. But her upright posture and gait raised new questions. How long had information technology taken to evolve the anatomy to residuum on two anxiety? What prompted some ancient ape to stand up upwards and brainstorm walking down the path toward humanness? And what kind of ape was it?

Lucy, of course, couldn't answer those questions. Merely what came before her? For twenty years after her discovery, information technology was as if the earliest chapter of the human story were missing.

One of the starting time teams to search for lucy's ancestor was the Middle Awash projection, which formed in 1981 when White and Asfaw joined Berkeley archaeologist J. Desmond Clark to search for fossils and stone tools in Ethiopia. They got off to a promising start—finding 3.nine-million-twelvemonth-former fragments of a skull and a slightly younger thighbone—merely they were unable to return to the Middle Awash until 1990, because Ethiopian officials imposed a moratorium on searching for fossils while they rewrote their antiquities laws. Finally, in 1992, White's graduate student, Gen Suwa, saw a glint in the desert near Aramis. It was the root of a molar, a molar, and its size and shape indicated that it belonged to a hominid. Suwa and other members of the Centre Awash project soon collected other fossils, including a kid'due south lower jaw with a milk molar yet attached. State-of-the-fine art dating methods indicated that they were 4.4 million years old.

The team proposed in the journal Nature in 1994 that the fossils—at present known equally Ardipithecus ramidus—represented the "long-sought potential root species for the Hominidae," meaning that the fossils belonged to a new species of hominid that could have given rise to all later hominids. The idea that it was a member of the man family unit was based primarily on its teeth—in particular, the absenteeism of large, dagger-like canines sharpened past the lower teeth. Living and extinct apes have such teeth, while hominids don't. But the gold standard for beingness a hominid was upright walking. Then was A. ramidus actually a hominid or an extinct ape?

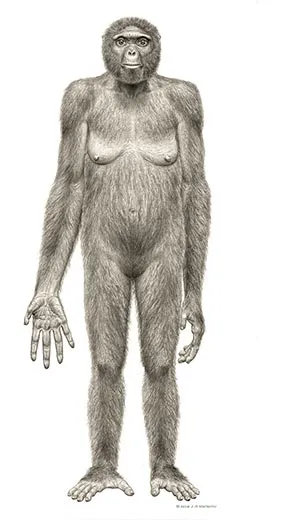

White joked at the time that he would be delighted with more fossils—in detail, a skull and thighbone. It was as if he had placed an lodge. Inside ii months, another graduate educatee of White's, Ethiopian paleoanthropologist Yohannes Haile-Selassie, spotted 2 pieces of a bone from the palm of a paw—their first sign of Ardi. The team members eventually found 125 pieces of Ardi's skeleton. She had been a muscular female person who stood almost iv feet tall but could take weighed as much every bit 110 pounds, with a body and brain roughly the same size as a chimpanzee's. As they got a good look at Ardi's body plan, they soon realized that they were looking at an entirely new type of hominid.

It was the observe of a lifetime. Merely they were daunted by Ardi's condition. Her basic were so brittle that they crumbled when touched. White called them "route impale."

The researchers spent iii field seasons digging out entire blocks of sedimentary stone surrounding the fossils, encasing the blocks in plaster and driving them to the National Museum of Federal democratic republic of ethiopia in Addis Ababa. In the museum lab, White painstakingly injected glue from syringes into each fragment and then used dental tools and brushes, oftentimes under a microscope, to remove the silty clay from the gum-hardened fossils. Meanwhile, Suwa, today a paleoanthropologist at the University of Tokyo, analyzed central fossils with modified CT scanners to see what was inside them and used reckoner imaging to digitally restore the crushed skull. Finally, he and anatomist C. Owen Lovejoy worked from the fossils and the estimator images to make physical models of the skull and pelvis.

It'south a mensurate of the particularity, complication and thoroughness of the researchers' efforts to understand Ardi in depth that they took 15 years to publish their detailed findings, which appeared this past Oct in a series of 11 papers in the journal Science. In short, they wrote that Ardi and fossils from 35 other members of her species, all constitute in the Middle Brimful, represented a new type of early hominid that wasn't much similar a chimpanzee, gorilla or a human. "Nosotros have seen the antecedent and it's not a chimpanzee," says White.

This came as a surprise to researchers who had proposed that the earliest hominids would wait and deed a lot like chimpanzees. They are our closest living relatives, sharing 96 percent of our DNA, and they are capable of tool apply and circuitous social behavior. But Ardi's discoverers proposed that chimpanzees have changed then dramatically as they have evolved over the past six one thousand thousand years or then, that today'south chimpanzees make poor models for the last common ancestor we shared.

In his lab at Kent State University, Lovejoy recently demonstrated why Ardi is and then unusual. He gently lined upwardly 4 bones from Ardi'due south mitt on his lab bench, and he showed how they fit together in a fashion that allowed Ardi's hand to bend far backward at the wrist. Past comparison, a chimpanzee's wrist is strong, which allows the creature to put its weight on its duke equally it moves on the ground—knuckle walking. "If yous wanted to evolve Ardi'southward hand, yous couldn't do it from this," he said, waving a set up of bones from a chimpanzee hand in the air. If Lovejoy is right, this ways Ardi—and our upright-walking ancestors—never went through a knuckle-walking stage after they came down from the copse to live on the ground, as some experts accept long believed.

As evidence that Ardi walked upright on the ground, Lovejoy pointed to a cast of her upper pelvic blades, which are shorter and broader than an ape'due south. They would have let her residue on ane leg at a time while walking upright. "This is a monstrous change—this thing has been a biped for a very long time," Lovejoy said.

But Ardi didn't walk like the states or, for that thing, like Lucy either. Ardi'south lower pelvis, like a chimpanzee's, had powerful hip and thigh muscles that would have made it difficult to run every bit fast or as far as mod humans can without injuring her hamstrings. And she had an opposable big toe, so her pes was able to grasp branches, suggesting she nevertheless spent a lot of time in the trees—to escape predators, selection fruit or even sleep, presumably in nests fabricated of branches and leaves. This unexpected combination of traits was a "shocker," says Lovejoy.

He and his colleagues have proposed that Ardi represents an early on stage of human evolution when an ancient ape body plan was being remodeled to live in two worlds—in the trees and on the ground, where hominids increasingly foraged for plants, eggs and minor critters.

The Ardi enquiry also challenged the long-held views that hominids evolved in a grassy savanna, says Middle Brimful project geologist Giday WoldeGabriel of Los Alamos National Laboratory. The Ardi researchers' thorough canvassing—"You crawl on your hands and knees, collecting every piece of bone, every piece of wood, every seed, every snail, every chip," White says—indicates that Ardi lived in woodland with a closed canopy, so footling light reached grass and plants on the forest floor. Analyzing thousands of specimens of fossilized plants and animals, as well as hundreds of samples of chemicals in sediments and tooth enamel, the researchers found show of such forest species as hackberry, fig and palm copse in her surroundings. Ardi lived aslope monkeys, kudu antelopes and peafowl—animals that adopt woodlands, not open grasslands.

Ardi is also providing insights into ancient hominid behavior. Moving from the copse to the ground meant that hominids became easier prey. Those that were amend at cooperating could live in larger social groups and were less likely to become a large true cat's next meal. At the same time, A. ramidus males were not much larger than females and they had evolved modest, unsharpened canine teeth. That'due south similar to mod humans, who are largely cooperative, and in dissimilarity to modernistic chimpanzees, whose males employ their size to dominate females and brandish their dagger-like canines to intimidate other males.

As hominids began increasingly to piece of work together, Lovejoy says, they also adopted other previously unseen behaviors—to regularly carry food in their hands, which allowed them to provision mates or their immature more effectively. This behavior, in turn, may take allowed males to grade tighter bonds with female mates and to invest in the upbringing of their offspring in a style not seen in African apes. All this reinforced the shift to life on the ground, upright walking and social cooperation, says Lovejoy.

Non everyone is convinced that Ardi walked upright, in part because the critical evidence comes from her pelvis, which was crushed. While near researchers concord that she is a hominid, based on features in her teeth and skull, they say she could be a blazon of hominid that was a distant cousin of our directly antecedent—a newfound adjunct on the homo family tree. "I think it's solid" that Ardi is a hominid, if you ascertain hominids by their skull and teeth, says Rick Potts, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian'south National Museum of Natural History. But, like many others who take not seen the fossils, he has yet to be convinced that the crushed but reconstructed pelvis proves upright walking, which could mean that Ardi might have been an extinct ape that was "experimenting" with some degree of upright walking. "The menstruum between four million to seven million years is when we know the least," says Potts. "Agreement what is a great ape and what is a hominid is tough."

Equally researchers sort out where Ardi sits in the human family tree, they concord that she is advancing central questions about human being evolution: How tin can we identify the earliest members of the human family? How do we recognize the first stages of upright walking? What did our mutual ancestor with chimpanzees wait like? "We didn't have much at all before," says Bill Kimbel, an Arizona State University paleoanthropologist. "Ardipithecus gives us a prism to look through to test alternatives."

After Ardi's discovery, researchers naturally began to wonder what came before her. They didn't have long to wait.

Starting in 1997, Haile-Selassie, now at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, establish fossils betwixt v.2 one thousand thousand and v.8 million years old in the Middle Brimful. A toe os suggested its owner had walked upright. The bones looked so much like a archaic version of A. ramidus he proposed these fossils belonged to her directly ancestor—a new species he eventually named Ardipithecus kadabba.

In 2000, Martin Pickford of the College of France and Brigitte Senut of the National Museum of Natural History in Paris announced their team had found an fifty-fifty older hominid—13 fossils representing a species that lived six million years ago in the Tugen Hills of Republic of kenya. Ii of the fossils were thighbones, including 1 that provided the oldest straight evidence of upright walking in a hominid. They named this fauna Orrorin tugenensis, cartoon on a Tugen legend of the "original man" who settled the Tugen Hills. Informally, in honor of its yr of discovery, they called it Millennium man.

Hot on the heels of that discovery came the well-nigh surprising one of all—a skull from Chad, nearly 1,500 miles west of the Great Rift Valley of eastern Africa where many of the most ancient hominids take been found. A Chadian student named Ahounta Djimdoumalbaye picked up a brawl of rock on the floor of the Djurab Desert, where windstorms accident sand dunes like waves on a sea and expose fossils buried for millions of years. When Djimdoumalbaye turned over the rock, he stared into the vacant eye sockets of an ape-like face—the skull of a primate that lived six million to seven million years ago on the shores of an ancient lake. It had traits that suggested it was a hominid—a pocket-size lower face up and canines and a skull that seemed to sit atop its spine, equally in upright walkers. Paleontologist Michel Brunet, then of the Academy of Poitiers in France, introduced it as the oldest known hominid, Sahelanthropus tchadensis. (Its nickname is Toumaï, which means "hope of life" in the Goran linguistic communication.) Just proving that a skull walked upright is difficult, and questions linger about whether Sahelanthropus is a bona fide hominid or not.

Taken together, fossils discovered over the by 15 years have provided snapshots of several different creatures that were live in Africa at the critical time when the earliest members of the human family were emerging. When these snapshots are added to the human being family album, they double the fourth dimension researchers can see back into our past—from Lucy at 3.2 million years to Toumaï at most 7 meg years.

I of the virtually sought-after fossils of that distant era was Lucy's direct ancestor. In 1994, 20 years later Lucy's skeleton was discovered, a team in Republic of kenya led by Meave Leakey (the wife of Richard Leakey) constitute teeth and parts of a jaw likewise equally two pieces of shinbone that showed the creature walked upright. The fossils, named Australopithecus anamensis, were 4.i million years old.

"This has been a fascinating 40 years to exist in paleoanthropology," says Johanson, "one of the great times to be in this field." Just, he adds, "at that place'due south still enormous defoliation" nearly the murky time earlier 4 million years ago.

One matter that is articulate is that these early on fossils belong in a grade by themselves. These species did not look or act like other known apes or like Lucy and other members of Australopithecus. They were large-bodied ground dwellers that stood up and walked on two legs. Merely if y'all watched them move, you would not mistake them for Lucy's species. They clung to life in the trees, merely were poised to venture into more open country. In many ways, these early species resemble 1 another more than than whatsoever fossils ever constitute earlier, equally if there was a new developmental or evolutionary stage that our ancestors passed through before the transition was complete from ape to hominid. Indeed, when the skulls of Toumaï and Ardi are compared, the resemblance is "striking," says paleoanthropologist Christoph Zollikofer of the University of Zurich in Switzerland. The fossils are too far apart in time to exist members of the aforementioned species, simply their skulls are more than like each other than they are like Lucy's species, perhaps signaling similar adaptations in diet or reproductive and social behavior.

The only way to find out how all these species are related to one another and to us is to discover more bones. In particular, researchers demand to find more than overlapping parts of very early fossils so they tin can be compared straight—such as an upper end of a thighbone for both Ardi and Toumaï to compare with the upper thighbone of O. tugenensis.

At Aramis, as soon every bit the clan leaders gave the Middle Brimful team their blessing, White began dispatching team members like an air traffic controller, directing them to fan out over the slope near Ardi's grave. The sun was high in the heaven, though, making it hard to distinguish beige os among the bleached out sediments. This time, the team found no new hominid fossils.

But ane morn afterward that calendar week, the team members drove upwardly a dry riverbed to a site on the western margin of the Heart Awash. Only a few moments after hiking into the fossil beds, a Turkish postdoctoral researcher, Cesur Pehlevan, planted a yellow flag amid the cobbles of the remote gully. "Tim!" he shouted. "Hominid?" White walked over and silently examined the molar, turning information technology over in his hand. White has the power to expect at a tooth or bone fragment and recognize almost immediately whether it belongs to a hominid. Later a moment, he pronounced his verdict: "very expert, Cesur. It's virtually unworn." The tooth belonged to a immature developed A. kadabba, the species whose fossils began to be constitute here in 1997. Now the researchers had one more piece to help make full in the portrait of this 5.8-one thousand thousand-year-old species.

"There's your discovery moment," said White. He reflected on the fossils they've bagged in this remote desert. "This year, nosotros've got A. kadabba, A. anamensis, A. garhi, H. erectus, H. sapiens." That's five unlike kinds of hominids, most of which were unknown when White first started searching for fossils here in 1981. "The Middle Brimful is a unique area," he said. "It is the simply place on the planet Earth where you lot can wait at the full scope of human evolution."

Ann Gibbons is a correspondent for Science and the author of The First Homo: The Race to Discover Our Primeval Ancestors.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-human-familys-earliest-ancestors-7372974/

0 Response to "Genealogies of the Early Families of Weymouth, Norfolk, Massachusetts"

Post a Comment